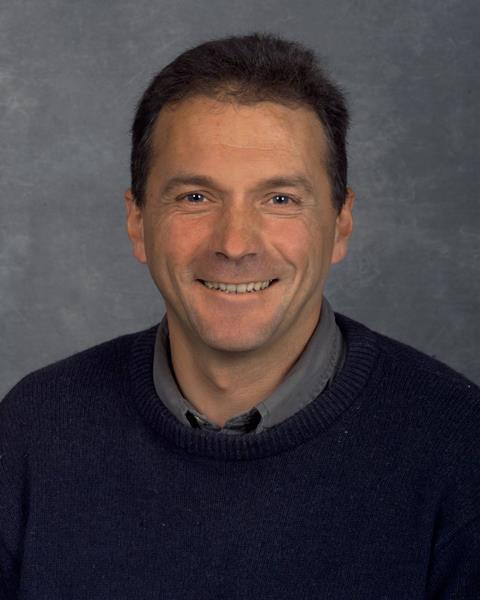

You probably have never, ever in your life heard about Victor Ninov. I know I didn’t.

Victor Ninov was a physicist originally working in GSI Darmstadt, a lab in Germany, during the 1990’s. He was an up and coming star in the element field, who specialized in Goosy, a revolutionary data analysis program, and had recently been named a co-discoverer of elements 110, 111, and 112, which was an incredible achievement that put him on the map.

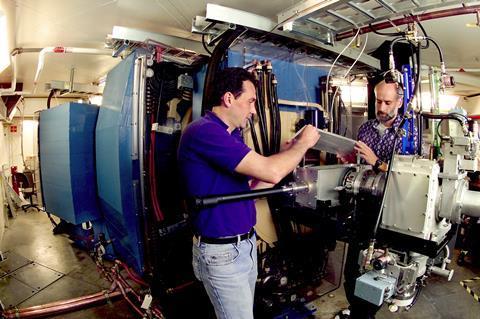

Ninov had been recruited by Darlene Hoffman and Al Ghiorso, who were the heads of the heavy element discovery team at the University of California Berkeley, a rival of his previous laboratory. After taking over in the 1940’s, during the Cold War, Al Ghiorso and his collaborator, Glenn Seaborg, had reshaped the periodic table and had established Berkeley as the most successful element makers of all time.

However, over time, Berkeley had diminished. It was being pushed out of the spotlight by its competitors GSI Darmstadt and Dubna. Even worse, through the 80’s and the 90’s, GSI Darmstadt had discovered elements 107 to 112.

Berkeley was desperate. Grasping on straws, they had decided to try a method that went against all conventional logic. Robert’s reaction, a simple reaction proposed by Robert Smolanczuk, consisted of bombarding lead-203 with krypton-86, according to The Element That Never Was by Kit Chapman, found on chemistryworld.com.

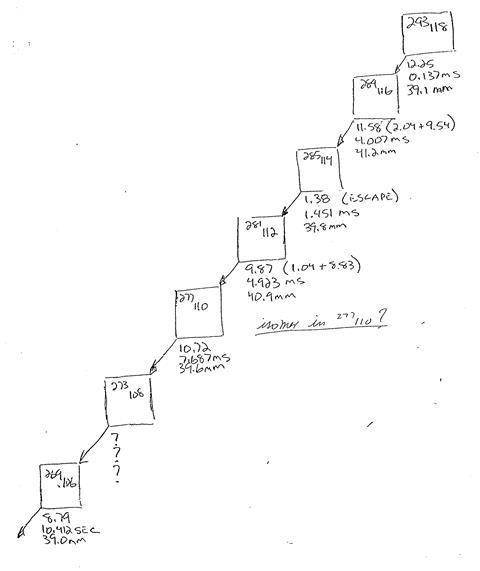

No one had genuinely believed that it would succeed, especially only after two weeks of attempting Robert’s unorthodox reaction. Yet, on April 19th 1999, Hoffman received a phone call from Ninov. He claimed that the reaction was a success, presenting three decay chains that showed the formation of element 118, before radioactively decaying into elements 116 and 114, on a singular, handwritten piece of paper.

Berkeley ran the experiment for another six days, and only discovered one chain this time. They had decided to proceed with publishing the discovery in Physical Review Letters.

It was a breakthrough like no other. Even if Dubna, Livermore, or GSI contested element 114, Berkeley had substantiating evidence of elements 114, 116, and 118.

Thus, around the world, various laboratories had begun to try replicating Robert’s reaction, hoping to see similar results.

Yet, no one could seem to attain the results Berkeley had with Robert’s reaction. Germany, France, and Japan had all tried to recreate the experiment, however they simply could not detect element 118. Ninov was not helping either, as his fellow scientists found him to be unusually avoidant during conferences, when asked about the elements.

In 2000, a baffled Berkeley had decided to attempt the experiment again and like the other laboratories, they could not detect element 118. Uneasy, Berkeley launched its own independent investigation, led by a nuclear physicist at Berkeley to check if something was wrong with its equipment. Nothing, but the possibility that the magnet settings could have been off, was reported. The committee recommended that the team complete an independent investigation of the old and new data sets, although this did not happen.

In April 2001, two years after the first test, Berkeley sought to rerun the experiment for a fourth time, attempting to remove all doubt. Miraculously, another decay chain for element 118 had appeared, according to Ninov.

However, by this time, other people had become proficient at utilizing Goosy. Various team members had reported findings opposite to that of Ninov’s. They found that in Ninov’s decay chain on Goosy, some events occurred much later, or rather were not even original events, but were implanted from another source.

They concluded that the 2001 chain was fake.

And this got Berkeley thinking, were the chains from 1999 fake as well? This was much harder to prove, as Ninov worked alone and hand-recorded results. The two hand-written decay chains by Ninov were the only pieces of evidence of their discoveries in 1999, and this was appalling. Another laboratory member checked the tapes that had previously only been viewed by Ninov, and came to the shocking conclusion that element 118 had never existed. Berkeley issued a press release and attempted to retract the paper, but the journal refused, according to The man that tried to fake an element by BobbyBroccoli, found on YouTube.com.

One of the co-authors, Ninov, still stood by his work.

The independent committee published its findings, and all the evidence pointed to one man: Victor Ninov. In a week, he was under investigation for scientific misconduct. Ninov maintained his innocence, but Berkeley disagreed, and found him guilty of scientific misconduct and dismissed him in 2002.

This case of scientific misconduct displayed gross negligence in Berkeley’s operations. No one checked Ninov’s claims, data, or even provided subsequent evidence. They trusted Ninov, and that was what brought upon their downfall.

Sources:

Chemistry World “Victor Ninov and the element that never was” (Article)

BobbyBroccoli “The man who tried to fake an element” (YouTube)

2019 The Regents of the University California (Photo)

2010 The Regents of the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley Nationa Laboratory (Photo)